Adapting Assessments for Adolescents

INTRODUCTORY

INTRODUCTORY

“You should look at this section if you have only a limited idea of the issues involved in assessing adolescents.”

Assessment of school students tends to focus on their skills and knowledge within academic subjects. As younger students grow older, however, a focus on subjects alone is often regarded as being inadequate. This is particularly the case when adolescents who are towards the end of secondary school are assessed. Instead, the focus on assessment begins to shift to consider the skills and knowledge that will help students who are close to becoming adults to navigate their adult lives.

This means that assessment programmes such as PISA do not only focus on skills in subjects such as mathematics and language. PISA targets students who are 15 years old and this means that in most countries they are near the end of compulsory education and may move into the workplace or further education.

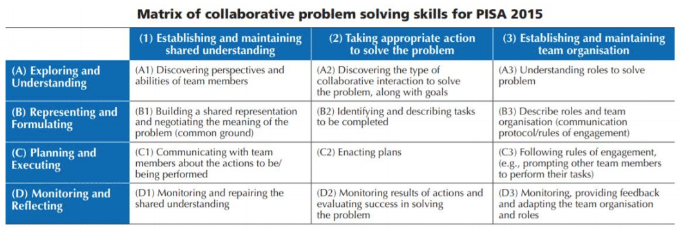

Hence PISA assessments include the assessment of skills and knowledge around domains such as learning strategies, financial literacy, collaborative problem solving, global competence and–in 2021–creative thinking.In illustration, the image below shows the constructs used in collaborative problem solving in PISA 2015 (https://www.oecd.org/pisa/sitedocument/PISA-2015-Technical-Report-Chapter-2-Test-Design-and-Development.pdf)

The innovative domains in PISA are partly influenced by the approach that the OECD uses towards assessing the skills of adults in its Programme for theInternational Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). PIAAC assesses the fundamental skills of literacy, numeracy and problem solving in technology rich environments and also collects information on how skills are used, not only at work but also at home and in the community.

The assessment of problem solving in PIAAC focuses on the cognitive dimensions involved, namely setting goals and monitoring progress; planning; accessing and evaluating information; and making use of information by selecting, organizing and transforming information. Assessment items are developed to reflect the context of an internet environment, a spreadsheet environment and an email environment, to reflect the ways in which adults are likely to undertake problem solving in real life.

Together, the innovative domains in PISA and the approach used to assess problem solving in technology rich environments in PIAAC are illustrative of how approaches to the assessment of adolescents need to take account of more than subject knowledge alone.

To find out more about approaches to assessing adolescents, go to #Intermediate.

INTERMEDIATE

INTERMEDIATE

“You should look at this section if you already know something about approaches to assessing adolescents and would like to know more.”

Adolescents–who can also be referred to as ‘young adults’–are on the verge of starting their adult lives. While end of school and university entrance examinations do still tend to focus on subject content, there is increasing awareness that this approach to assessment is inadequate. In a world where knowledge is available at the click of a mouse, and hence skills such as thinking, application, innovation, communication and collaborating with others are much more critical to future success, alternative approaches to assessment of adolescents are increasingly being used.

Adolescents–who can also be referred to as ‘young adults’–are on the verge of starting their adult lives. While end of school and university entrance examinations do still tend to focus on subject content, there is increasing awareness that this approach to assessment is inadequate. In a world where knowledge is available at the click of a mouse, and hence skills such as thinking, application, innovation, communication and collaborating with others are much more critical to future success, alternative approaches to assessment of adolescents are increasingly being used.

The approach taken by the OECD is to include so called ‘innovative’ domains in PISA. PISA is aimed at 15 and 16 year olds, many of whom will be about to enter the workforce. Hence in addition to assessing skills and knowledge in domains such as language and mathematics, the PISA tool includes assessment of areas such as problem solving and–in2021–creative thinking.

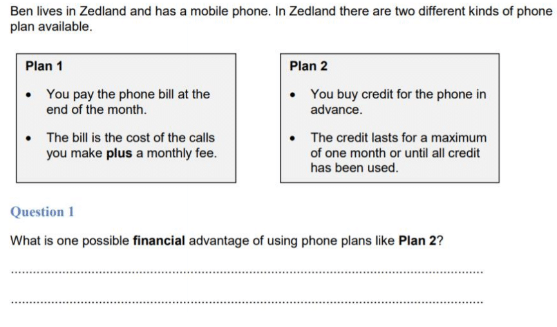

In PISA 2012, 2015 and 2018, the OECD included a module on financial literacy. This arose from concern that, although almost two-thirds of participating 15-year olds reported having bank accounts, many governments expressed concern about the financial literacy among their populations. Financial literacy was defined as “knowledge and understanding of financial concepts and risks, and the skills, motivation and confidence to apply such knowledge and understanding in order to make effective decisions across a range of financial contexts, to improve the financial well-being of individuals and society, and to enable participation in economic life” (https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/pisa-2015-assessment-and-analytical-framework_9789264281820-en).

In the assessment framework for PISA 2015, the content for financial literacy was defined as money and transactions; planning and managing finances; risk and reward; and the financial landscape. The processes include identifying financial information and analysing information in a financial context while contexts included education and work and home and family. In addition to measuring these cognitive domains, the contextual instrument collected information on elements such as access to money and financial products andattitudes towards and confidence about financial matters. An example item is shown below: (http://www.oecd.org/pisa/test/PISA2018-financial-literacy-items.pdf).

To find out more about approaches to assessing adolescents, go to #Advanced.

ADVANCED

ADVANCED

“You should look at this section if you are already familiar with approaches to assessing adolescents and would like to extend your knowledge”

As children grow older and become adolescents, the type of assessment that is appropriate to use with them also changes. Traditionally, almost all assessment used in education settings has focused on subject knowledge and skills within the lens of discipline. But increasingly there is recognition that the skills that adolescents need in life transcend a focus on subject. Instead, attention is being paid to the proficiencies that will help young adults to function successfully in their adulthood.

There is a great deal of debate about what skills and knowledge adolescents do need to have. One summary, the Australian Core Skills for Work Developmental Framework,(https://docs.education.gov.au/system/files/doc/other/1._csfw_framework_0.pdf) identifies the following three groups:

- Navigate the world of work– Manage career and work life; Work with roles, rights and protocols

- Interact with others– Communicate for work; Connect and work with others; Recognise and utilise diverse perspectives

- Get the work done– Plan and organise; Make decisions; Identify and solve problems;Create and innovate; and Work in a digital world.

In terms of assessing such skills, there are three prominent examples. First, the OECD’s PISA–which is taken by 15 and 16 years old students-includes not only a focus on subjects but also on innovative domains such as problem solving, financial literacy and–in2021–creative thinking.Second, the OECD’s PIAAC–which is taken by adults–includes literacy and numeracy as well as components such as problem solving in technology rich environments and also collects information on how skills are used, not only at work but also at home and in the community.

The third area of innovation which is relevant to the assessment of adolescents is in the vocational education sector. While in some countries vocational education is regarded asa very poor second runner to higher education, in others it plays a highly regarded role as an equivalent pathway to skilled employment. Assessment in vocational education includes entry to, progress through and graduation from vocational programmes. Vocational assessment also includes screening entrants to vocational careers.

The focus of assessment in vocational education includes the knowledge, aptitudes and attitudes that are required for relevant professions. Assessment tends to comprise a combination of written assessments, performance tasks, projects and portfolios of work. A common strategy in assessing students in vocational education is to present them with areal world scenario and ask them to respond (this can be done on paper and also via performance and projects).

The simulation of real occupational settings is a critical way of identifying professional judgement and is also commonly used in medical education assessment. For example, the Health Practitioners Admissions Test for those who wish to study to become an allied health professional includes a Test of Interpersonal Understanding with provides scenarios to test takers and asks them to respond (https://hpat-ulster.acer.org/).

As assessment for adolescents evolves over time, we should expect to see a great deal more focus on measuring the ways in which students respond to real world environments as a way of assessing their readiness for work, further study and their future lives, particularly through drawing on the possibilities offered by digital and virtual reality assessment to provide them with stimuli that are life-like and engaging.

About the guidance levels